Summary

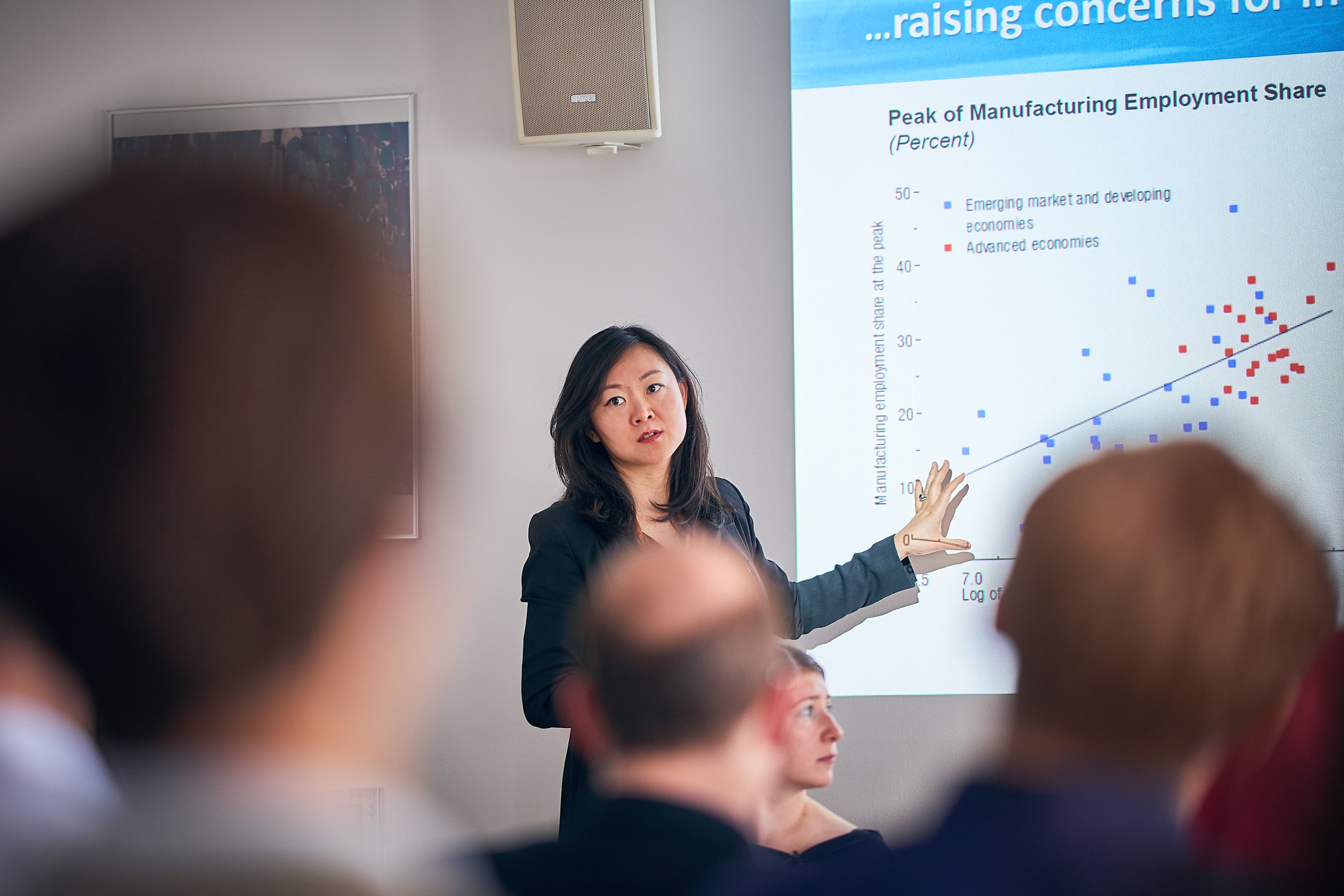

The global economic recovery has strengthened, but the risks that long-term growth will be weak persist. How can countries deal with the challenges of population aging, a declining manufacturing sector, and weak productivity trends? Ms. Zsoka Koczan and Ms. Nan Li from the IMF presented the major findings on these subjects from the latest World Economic Outlook.

On May 4, Ms. Zsoka Koczan and Ms. Nan Li visited the JVI to present two analytical chapters they co-authored in the new IMF World Economic Outlook. While cyclical upswing and recovery in investment might help raise potential output, weak productivity trends and slowing labor force growth due to population aging undermine the prospects for long-term growth, especially in advanced economies. These issues are the focus of the analytical chapters.

Chapter 2, presented by Ms. Koczan, highlighted drivers and prospects for labor force participation in advanced economies, where population growth is slowing and the number of elderly people is rising. It is projected that by 2050, the population will be shrinking in almost half of the advanced economies, with old-age dependency ratio doubling from the current levels. These developments could slow economic growth and in many cases undermine the sustainability of social security systems.

So far, many countries have been successful in containing the effect of population aging on labor supply. In half of the advanced economies, labor force participation has actually gone up since the global financial crisis. Participation by women, and recently by older workers, has increased considerably, while participation by prime-age men, especially those less educated, and young workers has declined.

For men, the drop in participation can largely be explained by aging and the global financial crisis. For women and older workers, however, most of the dramatic increase in their attachment to the labor force is associated with gains in educational attainment, structural transformation and changes in policies and institutions. Notably, family-friendly policies help to raise the participation of women, and changing retirement incentives against the backdrop of increased life expectancy tend to keep older workers in the work force for longer.

For the future, Ms. Koczan highlighted the considerable scope for policies to counteract the forces of aging by enabling those who are willing to work to do so. Investing in education and training, reforming the tax system, reducing incentives to retire early, policies to improve the job-matching process and to help combine family and work life can all encourage people to enter and remain in the workforce. She warned, however, that those policies are not likely to be sufficient to fully offset the dramatic demographic shifts. Thus, to boost their labor supply many advanced economies might need to rethink immigration policies.

Technological advances also have negative effects on employment, especially in manufacturing. While policy measures can help redirect labor force to other sectors, the concerns about manufacturing are about more than employment. Chapter 3, presented by Ms. Li, considered the implications of manufacturing jobs for productivity and inequality.

Ms. Li noted that manufacturing has been fading as a source of jobs in many countries, while the service sector has expanded. Thus, in advanced economies employment is shifting from manufacturing to services, and in developing economies from agriculture to services, bypassing manufacturing.

This raises concerns about future growth and inequality; historically developments in manufacturing coincided with the growth of productivity and income in many countries. Globally, however, the share of manufacturing in employment and in output has been broadly stable since the 1970s. These developments reflect a change in the composition of global manufacturing employment in favor of developing economies, where output per worker tends to be lower.

A shift in employment from manufacturing to services need not hinder economy-wide productivity growth. There is substantial overlap between productivity growth among manufacturing and service subsectors, so some service industries have higher productivity growth than manufacturing overall. Moreover, productivity in services tends to converge to the global frontier—the levels seen in the most productive countries.

With respect to income inequality, labor income in manufacturing is somewhat higher and more evenly distributed than in services, but skill premium appears to be a more important factor. Changes in aggregate inequality are thus mostly explained by rising inequality within sectors.

In future, however, it is unclear whether the service sector productivity trends will continue to hold or whether they were a byproduct of a temporary boom in demand. Given these uncertainties, Ms. Li concluded that supporting equitable growth would be better served by policies to raise productivity across all sectors and make gains from higher productivity more inclusive via targeted redistribution policies and safety nets. It will be crucial to facilitate the reallocation of labor to sectors with higher productivity growth, to remove barriers to entry and trade in services and to support the reskilling of workers affected by structural change.

During the Q&A session that followed the presentations, the discussion touched on employment prospects in manufacturing and the role of demand for services; co-movements of productivity and wages; sectoral and geographical mobility; competition and production chain links between manufacturing in advanced and developing economies; new skills and comparative advantages that demographic changes can bring. When discussing policies for keeping elderly people in the labor force, the presenters noted that life expectancy has a positive effect; health may be important but is hard to quantify. In comparing market to nonmarket services, they said, the former tend to grow faster, but data on the latter is less reliable.

Alexei Miksjuk, Economist, JVI